It was with some relief that I discovered that the Midland Beach Turtle site was used for a community gathering after the storm, as it was mostly intact.

|

I have a few sculptures on Midland Beach, Staten Island. I know that the area was devastated in late 2012 during Hurricane Sandy. Perhaps because of the protective effect of Sandy Hook and Breezy Point, the damage to the area was more flooding than impact damage. Still, many homes were devastated. For the last two years I've wondered how my big Sea Turtle sculpture fared. It's right on the beach, on a lovely multi-coloured pad. I feared that the pad, at least, had been torn up by the storm surge. The turtle weighed most of 500 kg, so I thought it might have stayed upright. It was with some relief that I discovered that the Midland Beach Turtle site was used for a community gathering after the storm, as it was mostly intact. It's fun to think of this as a community gathering place, as well as a cool place to get wet. Here's another view. Kids playing in the fountain. It's funny to think that my daughter, Caitlin and I sweated through a heat wave to make this sculpture. I modelled this directly in epoxy clay, which, at 38C, was setting unbelievably fast, forcing us to work at a feverish pace. We're both relatively skinny to this day. It looks like the nearby pier, Ocean Breeze fishing pier, the largest pier on the Atlantic remained intact. In 2003 I made the tooling for the fishing rod holders. Did we cast these in aluminum? They must be well coated to avoid corrosion from the salt water. The Ocean Breeze pier was closed for some months, but the main damage to the area seems to have been displacement of ramps and railings. So many residents in this neighbourhood had their homes destroyed that it's hard to imagine the area rising from the damage, but I guess it has. It is a relief to know that the public elements remain intact to provide those important gathering places.

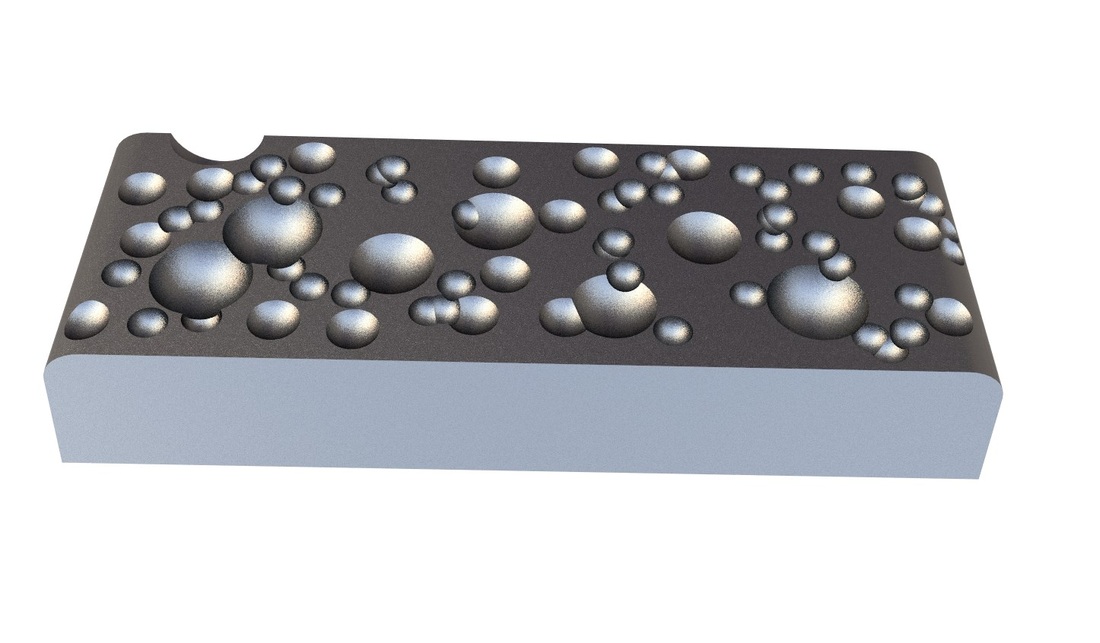

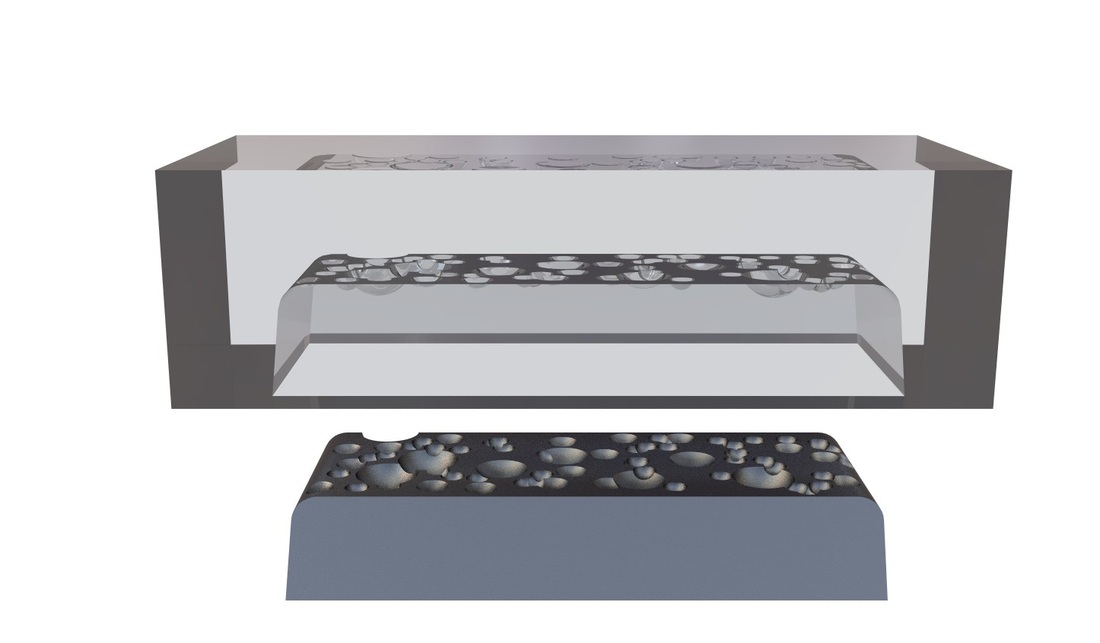

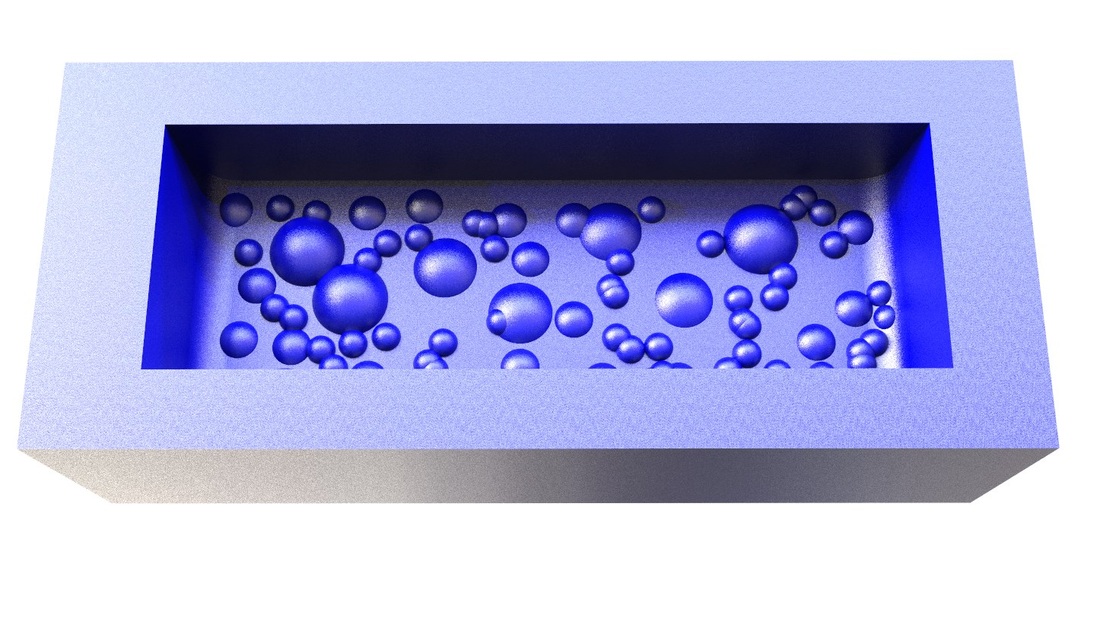

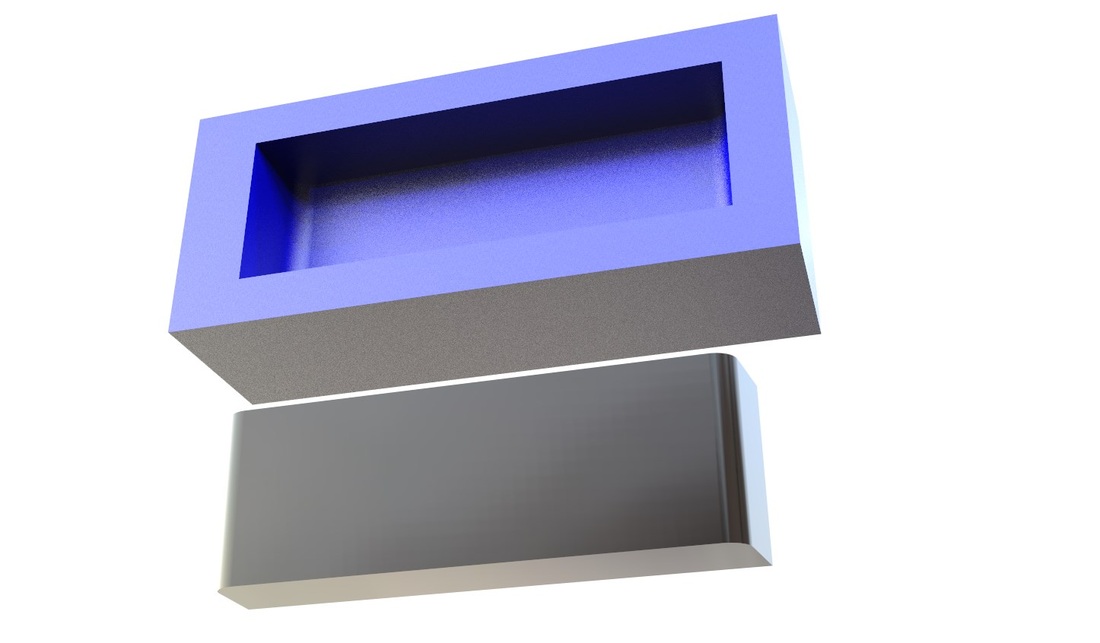

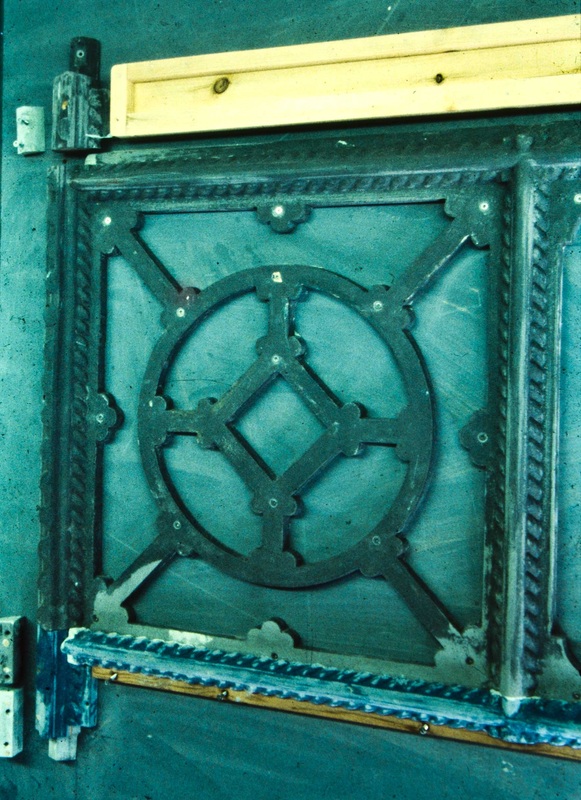

Perhaps digital scanning and additive prototyping will become more sophisticated, replacing my old fashioned hands-on work, but here's how I have recreated decorative cast iron objects: This illustration represents a flat surface that is badly pitted and rusted. You can imagine swirls of acanthus leaves, grape clusters, or even cherubic faces, quite complex surfaces being this damaged by time and atmosphere. There would formerly have been lines and smooth transitions defining the surface. The great thing about cast iron is that it came from a moulded surface, so finding parting lines and taking moulds from the surface is relatively easy. I have made the mould transparent to illustrate that the mould picks up all the detail from the surface. I wax the surface quite thoroughly and pour a quick-cast polyurethane over it to create a rigid, sandable surface. I use Repo One from Freeman, a nice, predictable two-part urethane, one that keeps really well, without reacting to the atmosphere. Many other resins start to go crusty and bad within days of opening the container. Here's the plastic mould, shown open. Note how all those pits have become raised bumps. The original surface gradually became more and more pitted. The mould can now be sanded, removing that damage while following original lines and curves. I've worked a lot in the negative, as it's a great way to make detail come alive. A typical surface, an historic iron gate or post might require many hours of sanding to level out the damage. And here's the sanded mould in blue, with a copy taken in plastic. This copy is used to produce the new cast iron reproduction.

In reality, there might be some hours of work on that plastic copy, fairing lines, cutting in lowered detail that was lost, and sharpening features. One of our Fathers of Confederation and Globe newpaper founder, George Brown, built his home in Toronto in 1874. It was common for ships travelling back to Canada after delivering loads of timber to return with holds weighted down with cast iron objects. It does imply here, though, that Brown had a hand in designing the fence, so perhaps this was locally made, though I suspect that the castings were somewhat more sophisticated than those produced in most of the area foundries. In the late 1980's I was commissioned to restore the fence, working from the well-rusted and pitted remains of the various bits of the fence. Some sections, perhaps inches across, were missing altogether. It was my job to figure out how the fence was made in the first place, where the parts came together, and how they were cast. That heavy rope motif top rail was hollow to incorporate a long pipe that supported the various panels. It's pretty hard to weld cast iron, especially if you're a 19th century blacksmith. The original castings were quite thin, leading me to think that these were cast with some skill. The thin parts, of course, were the area most rusted and broken. This is the curly decoration on top of the posts. This arrived in about 4 pieces. One piece from the original is shown here. I roughly assembled what I had, took moulds off these parts, and added carving to fill in the blanks. To make this work in the foundry, I had to produce "tooling", the grey board shown. This gets placed in a metal box, and sand is rammed around the pattern to form a mould into which molten iron can be poured. Here's another view of the restored fence. Each panel consists of the main panel, top finials, the rope motif top rail, and a cap for the bottom rail. There are pipes running along top and bottom, hidden inside the castings. The whole thing is bolted together. This is the panel tooling in progress. I would have started by filling in some of the surface pits with clay, then taking moulds off both sides of the surviving iron panel. The mould would have projecting bumps where the iron surface was pitted. I would have spent hours sanding these bumps off, effectively rebuilding the surface. When I took copies out of the moulds, I would further refine the surface to get pretty close to where the casting started out 110 years ago. Here is a piece of the main post, perhaps already somewhat cleaned up. Occasionally, on restoration projects, I can slather on a plastic filler and sand it smooth. Other times I have to return original pieces untouched. Or appear to be untouched. Here is half of the post pattern. I've smoothed the surface and added 'prints' top and bottom. To make the post a hollow cylinder I have to generate a separate box that creates a sand form that fills the interior of the casting. Those 'prints' support the sand form, the Core, in the main mould.

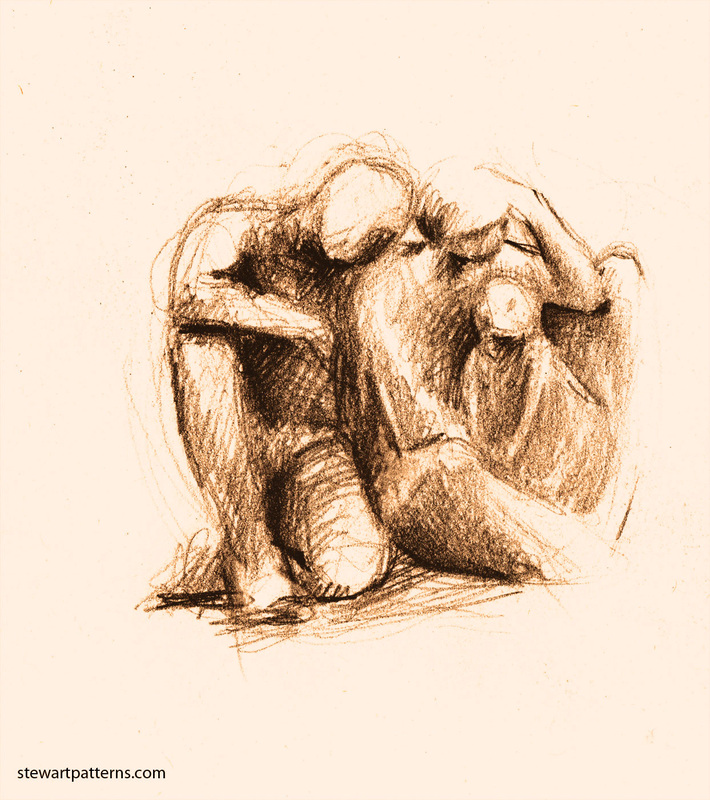

There are often long discussions that accompany a project like this. We have to figure out how to hold the whole thing together, often trying to improve on the original structure. We have to make the patterns work in the foundry. On a job this big, there are some dozens of small pieces to be cast, so I might be asked to make a tool that makes multiples of the part to keep the cost down. It's fun to be part of this kind of effort, connecting, in a way, with the original builder and foundry guys, making something that might extend the life of this bit of history for another century or so. I can blather on forever about stones, and will do soon. Early in my career I was always trying to include my love for natural textures in my work. And the Mother and Child motif was always a favourite, too. I still like it. Therapists? Got any theories? I showed my work for some years, early on, in Art in the Park, Stratford, Ontario A kindly Torontonian, quite a sophisticate, bought one of my first Mother and Child bronzes. I had admired the work of Mathias Mulume, and wanted to incorporate some of the textures that I found in nature, and in his work. The kindly Torontonian came back a few weeks later and said that she'd like a large piece for her foyer. I guess I must have visited her home to see the space. She was European, decorating in that cool, white, sparse way, everything rather crisp and clean-lined. She said the fateful words that artists might love to hear, something about liking what I did, to make this perhaps 7 feet (213 cm) long to be mounted in a long high-ceilinged room lit by a long skylight. It was a perfect white stucco wall. "You know what I like" I felt like I'd been treated like a real artist, at last. I'd made it! Someone trusted me! I don't remember if I ever submitted as much as a thumbnail sketch. Maybe. This was long before the internet, so tossing ideas back and forth wasn't the effortless thing it is now. I simply went ahead. If I ever offered to show the maquette to this customer, the idea must have been dismissed. Or maybe I was just in some euphoric fog, a favourite place to hang out. But I just went ahead and played for hours, adding texture to my plaster master. I had this cast locally, and was quite pleased with myself when I presented this to the customer, standing in her immaculate entry, feeling like the artistic master at his patron's castle. I think I had a template ready for drilling 4 large holes for substantial anchors into that wall. Perhaps we spent a short while finding just the right spot. I drilled the holes, inserted the anchors, and hung the sculpture.

The nice lady looked serious for quite a while, then said: " I don't like it" Yikes. Being a well-brought-up fellow, I did not go ballistic. I simply offered to take it away. She was quite contrite, not wanting to do harm to a penniless artist. Still, she nodded, and asked me to take it down. It took seconds. A couple of lifts to remove the bronzes, a few yanks to pull out the anchors. Then she said: "what about those holes?" I've always been pretty handy with tools. A few holes in drywall have never been a problem in my world. Everyone I know can slop in a little Polyfilla as required. I said that any local craftsman could fix this for her in a few minutes. She looked quite worried for some time. I let the silence hang until she said: "Put it back." I was astounded. I think I might have asked for clarification. It was true. She wanted me to put it back. I did. I got paid. I went away, no longer some high-flying artist, but a man who installed really expensive drywall compound. Over the years, my proposals have gotten more and more explicit. When fax machines came out, I could submit drawings and quotes in real time. I grabbed on to the internet fairly early on, appreciating the ability to submit photos of work in progress. I don't swagger as much, nor do I fall down in horror or amazement. Life is more boring, and this is good. It's the later 90s, I'm working pretty steadily, with and without assistants, making foundry tooling, industrial stuff and the occasional more artistic thing, a reasonably steady flow of smallish work. I had a customer of long standing, Trystan, who had started doing trade shows in the US. Trystan makes 'site furniture', or outdoor amenities like benches, tree grates and fountains. I had done all their masters and tooling for cast iron and aluminum since they got started in the early 80s. They sent a thumbnail of a hare jumping over a tortoise, wondering what it would cost to get this done about 9' long in cast iron. It has always been my practice to try to add value to customers' ideas. I figure that if I give away some expertise off the top that I will show that I have the chops, and that I'm happy to collaborate. I wrote this back as an aluminum casting, cutting the cost substantially, adding other ideas to make it fly. The rabbit was going to be mounted on a pole, and I was really nervous about the idea of kids jumping up and down on that long fulcrum. I did get the job. It was pretty exciting. Up here in the Frozen North, New York seems like a big deal. They were trusting me to do this sort of grand, sort of cartoonish project. The landscape architect for the NYC parks system sent a clay maquette, perhaps 17" wide for me to work from. I have no idea how I quoted this job. I guess I just figured out surface area and threw some guesses into a hat. I planned to build this directly in epoxy clay, cutting it up for foundry patterns. It seemed like a brilliant idea, at the time. I hired an assistant. We spent untold hours building the original in styrofoam, shaping as close as possible to the final surface. I added plaster on top, making the surface smooth and even more detailed. I waxed the surface and started laying epoxy clay on top, gauged by eye to be roughly .3" (8mm) thick.

Here I have established some templates, plywood outlines that define cross sections. I am filling in with styrofoam. I kept two glue guns going. A variety of nail guns and those hot glue guns help to keep the building process moving quickly. The shaping of the bulk of a piece often goes really quickly.

This is the time when I feel most competent, mainly because I can start with nothing and build this turtle shell until it looks not bad in a matter of hours. I might swagger a little on the way home.

When I am building foundry patterns directly, I have to create a hard, durable shell approximately the thickness of the bronze casting, something like 6 to 8mm. This means getting the surface underneath pretty accurate. And trying to get customer approvals on the shape before adding final detail. I would push really hard to get this approval, and fail, every time.

Don't try this at home: endless mixing of epoxy and micro beads to get clay that sets pretty quickly, forcing me to work really quickly, especially if it's hot. Then there is a lot of sanding to improve the shape and get those foundry patterns to work in the foundry. I suspect that at this point I've already spent the money designated for labour. I have skipped over another 150 hours of messing with plastics to make the parts of the piece fit into the foundry. It's best glossed over. Jeepers, I could have been learning the violin or studying law... Here we are, grinding the castings that have been welded together. Lots more shaping with the 4 1/2" angle grinder. This is not fine sculpture. But it's Aesop for New York. At the time, I still felt excited and, well, important, perhaps. Somebody had posted the location of the sculpture on Google Maps. I did visit this location in the summer of 2001, a few weeks before the world changed. I guess my life changed a bit when this project came my way. The designer was happy with our work. He asked, at some point, "how high is the ceiling in your studio?", and for the next decade or so I did a number of 10' (3m) high Park Features for the NYC Parks Dept. The elation over working for the city lasted for a while. Still, my hands would ache when I got the subsequent calls for more stuff. The challenges just got bigger, and I didn't get smarter quite as fast as I'd have liked.

As a guy who claims to be self-taught, I've had a number of mentors. A dirty, hot, noisy business like the foundry would seem to be populated with rough folk, reticent, even cranky. Generally, I have found the opposite. I'll pause in a day and swap recipes with a guy dressed in protective gear, face covered in smoke and grime. I'll discuss wine favourites with a fellow who probably didn't finish grade 10. When I showed interest in foundry ideas many years ago, the local foundry owners and workers seemed all too happy to help. I was just a starving woodcarver who wanted to cast stuff. Before I knew it, I was in the foundry world, carving various objects for casting in the memorial and giftware field. Every project I brought in for casting would bounce back at me for modification. It was a long journey, learning to prepare three dimensional work for casting. Still, I was a woodcarver with two hungry kids, a guy with one small gig. It was learn or go and work at Home Depot. I was sort of raised in the business by the original owner of Riverside Brass, right across from my studio in the late 70s. Subsequent owner/managers have been great mentor/collaborators. About 10 years ago I was approached by Artcast to mentor a young sculptor from St. John's Newfoundland. He had created his own project, found his own funding, and was looking for a way to cast this large piece in bronze. Artcast thought he might benefit with a little help creating the master pattern. Morgan MacDonald arrived in January and spent much of the winter in my studio. Morgan turned out to be an amazing anatomist. I had little to suggest in the way of improvements. As I remember, he just worked steadily away, learning my tricks with styrofoam and wax, but mostly bashing away on his own. My studio was big enough that I could do my other work around him. There are some good photos of the casting in process at Artcast, and some shots of the unveiling here on Morgan's site. It's been fun, working with other artists. It was always a challenge working with assistants, as I don't have the policeman gene. If helpers were going to survive in my studio, they would have to love working alone, coming and going according to the workload and the challenges of the day. I liked the teaching part. So, now I just teach for fun, and work alone. It's better for business!

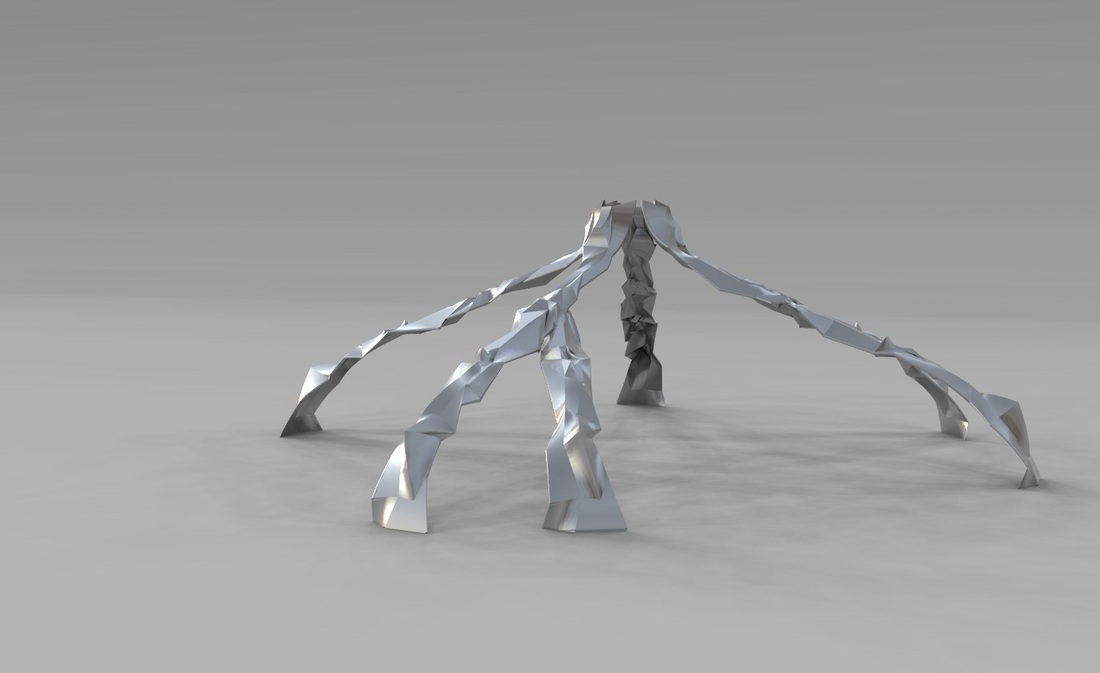

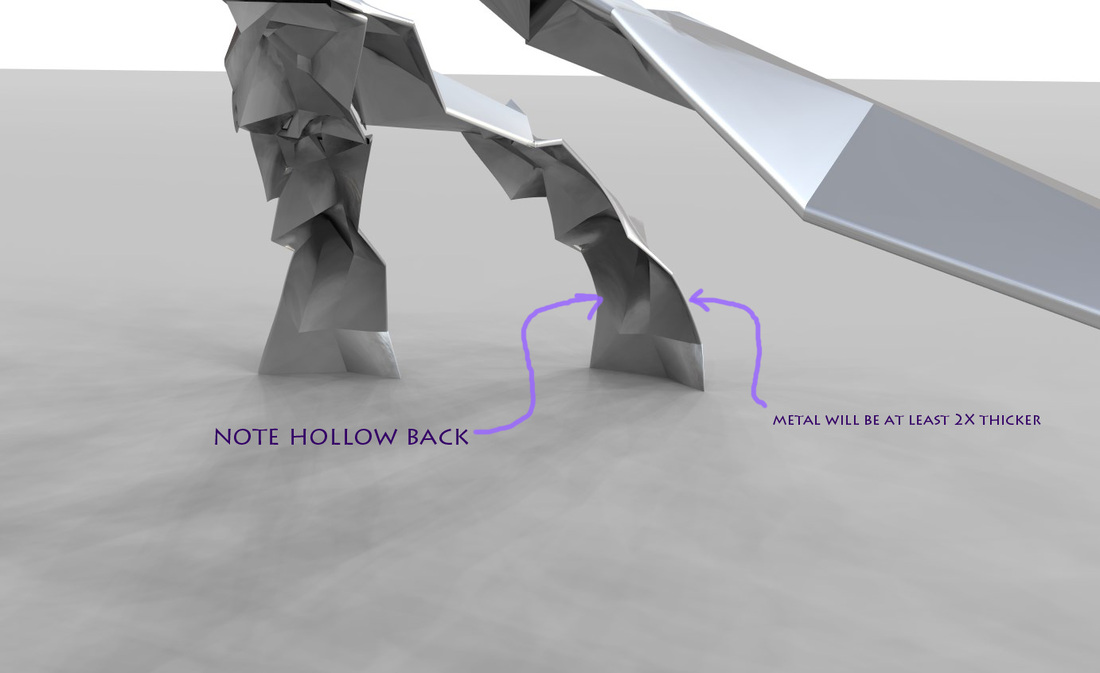

Still, I think I've added to the creative community a little and hope to do more. There is always hope that those that follow will do things with less struggle, fewer mistakes. I'm often looking at project postings on Custommade.com, a place where people look for solutions to their furniture and jewellery ideas. I came across a person in Oklahoma looking for someone to approximate a design for table legs. The original was done by Adam P. Gale in California. These were made from sheet stainless, assembled, welded and polished into a solid-looking random surface. These look to be done beautifully, but they were out of the person's budget at US$40,000 for the legs. I understand the price: this is a huge project. The table is most of 8 feet long.

So, this is one of my favourite things, designing within parameters, price, materials, finish, weight. I thought I could cast these in aluminum with some substantial change to the design, while, perhaps hanging on to some of the sense of 'roots'. It's taken some weeks of playing with ideas inside Rhino 3D. I had to learn how to generate connected planes and be able to move them around together, then creating the look of a solid. It was fairly easy, in the end, but we generalists learn slowly. The potential customer contacted me again today, so I've just stopped carving a portrait, slightly tedious work, plugged in my headphones to Songza, and got to work at the computer. Sigh, it's just a lovely thing to do in this little life. I'm at a standing desk, brain alight, dancing a bit to Songza, looking occasionally out into the trees and sunshine. Here's what I sent to the customer: The first morning in Croatia, in Split, I woke up to this sound, just meters away, the voices echoing around the ancient walls of Diocletian's Palace. This video shows it perfectly, way better than I got. I ran to that spot, navigating by ear down endless narrow corridors, open to the air, until I found this. It was one of those "stop my life, I'm OK right here" moments. Graeme bought a couple of bikes, and we spent many happy, strenuous hours exploring the coastal hills near Split. I knew that my earliest inspiration, the sculptor Ivan Meštrović had worked nearby, but, perhaps in the overwhelming visual banquet of the area, I just didn't think to look up local references. We were just out biking another area north of the city when we came across the museum. Well, we were on Šetalište Ivana Meštrovića, Ivan Mestrovic Promenade, so there might have been a clue. Not sure. It was hot out there. We were sun-blasted and salt-saturated, thanks to the local cuisine. We came to this. Not the studio of a starving artist: The gate was locked. There was a lady selling tickets and memorabilia nearby, who said the gallery would open in an hour or so. I can't remember if she could communicate that there was more down the road, or whether we just drifted there. But we drifted. And found another gate, with Mestrovic on it, pretty much unguarded, deserted, in fact. We wandered in, through a portal into a mostly empty walled courtyard, and into an open door. I may have almost fallen down. This was just available to anyone on the street? I'd languished over these pieces for hours in my early 20s, and here they were, all of them:

I did spend quite awhile with these bas relief carvings. The texture, the rich aged wood, those dramatic Slavic poses, the Medieval style fascinated me as a young man. Maybe, as it just occurs to me, this shouted to me 'you want to be a dad'. I became a dad. I took my son to see these. I was impressed. He was patient.

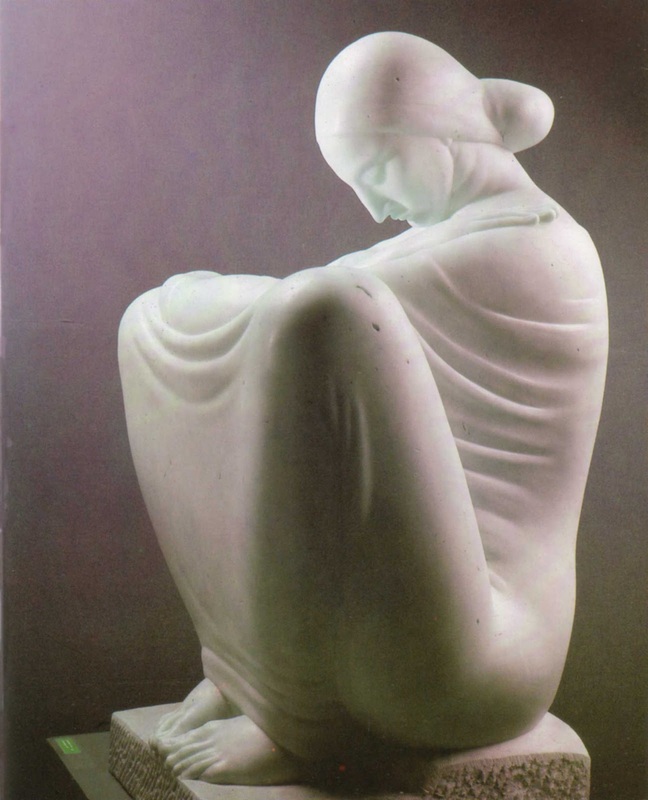

Perhaps I just have spent so much time in the company of wood, carving, sanding, finishing, breathing the stuff, knowing what I'm working with just by the smell, that I can look at these and get a certain happy fatigue in my hands. I know the sound of the studio when these were made. It's been years, though. I starved during the time that I was carving. I still have racks of tools, but they have been used for other less noble purposes, and wouldn't sing through wood without a lot of attention from stone. We did get to the Mestrovic Gallery. Graeme waited patiently while I hung out with the many stone sculptures that I'd known from the Mestrovic book. It was a bit like the few moments that I'd stumbled into the Louvre, just before they closed, finding an Etruscan sculpture, the original of the one featured on our Grade 9 French textbook, only there were perhaps 20 works that I'd ingested and added to my emotional waistline. Perhaps that was enough of a pilgrimage. I'd been back to my early 20s. I had knelt, paid my respects to a master. Graeme and I wandered to various harbours in the Dalmatian Islands riding the rocky lanes, eating in tiny cafés in narrow streets, and eating all the gelato we could find. It was a sweet time, sweaty, too. The hard work of many hands was simply everywhere:

This is Skrip, located at the top of a very long goat path. Graeme and I struggled up this route, spending hours grunting, swearing and laughing at each other, pushing our bikes over a lot of rough ground. When we arrived at the church, an elderly lady came out of the shadows and motioned me through the heavy oak doors of the castle, gesturing to graffiti carved into the wall by some bored Roman. She sold me some local Rakia, in a pop bottle, all kinds of herbs floating in the local spirits. Going home, we had a smooth paved road. We drank beer on the coast at Supetar, exhausted and jubilant and left the rakia mostly alone.

When I was 23, I was pretty much lost, like lots of young men. Being lost, though, was not my forté. A Plan could keep me safe, somehow. I'd quit physics, quit music. I had to make a living. I'm not sure how long it took for the light to come on, weeks, perhaps? I had a cousin Karen, my age, a potter, working nearby. I'd been a busy student so I had sort of lost touch. A visit to her studio near Beamsville, Ontario was revelatory. A person could make something with his hands and sell it for money! Amazing! I suppose, being the son of a civil servant, I was not well set up for self-employment, but it seemed perfect, a way to control aspects of my life that seemed to need controlling. I guess I'd been carving something all my life: figures in firewood, faces in clay, people in chalk (French class), a lute player in soapstone. Where is that little thing now? I spent a lot of time in the library in St. Catharines, Onario. I had found a beautiful book dedicated to the Croation artist Ivan Meštrović, born in the late 1800's, a sculptor who was quite famous in his time, but seems to be rather obscure now. I spent hours poring over his work.

... and I've had this ongoing fascination with bas relief. No explaining that. The warmth of the wood soothes some hollow place, too, calms something that begs nurturing. I'm not schooled in art history, but I see elements of Gothic figures here, a taste of Egyptian, some art deco, a bit of post-impressionism. I see a bit of Kathe Kollvitz.

For the first few years, I made my living carving gnomes into old pine roots. I could bash a bunch into that fragrant wood, put them into a cloth bag, and cart them off to a mall and sell them. My first day I made $55, a fortune, given that I was doing casual labour, working a moving van, wielding a jackhammer for less than $2 an hour. Still, whenever I could, I carved larger reliefs. They all sold, probably for a lot less than they were worth? Certainly, as some of that wood was solid teak and Honduras mahogany, the materials alone would be worth many times the original selling price. So, in 2007, when my son Graeme had a holiday from his job as foreign correspondent for the Globe and Mail, posted in Kandahar, Afghanistan, we decided to meet in Croatia for a bike holiday. The idea of cycling down the islands of Dalmatia from Split to Dubrovnik seemed terrific. It was lovely to spend two really active weeks with Graeme, eating gelato, wandering among Roman ruins, riding endlessly up steep hills, and talking, talking in a way we hadn't in a decade. I made a great discovery for me, a kind of revelation, stumbling over a huge collection of Meštrović work, almost everything I'd been dreaming over 30 years earlier.

I'll rave about that in the next post. I'm skipping a massive amount of effort here, work done at Artcast. The video, in the first minutes, gives you a bit of an idea of the amazing skill required at the foundry. By the end of May, 2005, the extensive landscaping and installation was done, placed in Stewart Park, Perth, Ontario. Click here for the street view. There was a huge event planned around the unveiling. There was a day-long open house at Millar Brooke Farm that included the RCMP Musical Ride. My 88 year old Mom was there, thrilled with the show. Cousins, an elderly aunt, neighbours, in-laws, my brother, nieces and nephews were all in attendance. It was hard to know where to put a little attention. It was a funny moment, the actual unveiling. Ruth, Jean and I were poised, with some trepidation, on the front edge of the crowd, watching the cover come off. Lots of applause. Breath held, is this our moment? Thus, the unending lack of understanding about what we were doing. That feeling might have been mostly mine, not being a horse person. I'll have to ask Ruth about unveiling her portrait of Ocar Peterson with the Queen in attendance. She might have had a similar experience: The cover came off. Applause, long speeches from many dignitaries. No mention of the artists or the foundry. Perhaps, for my Mom's sake, I wish there had been a wee nod. Still, I suppose I never made a wrong move, in my Mom's eyes, so it didn't matter. This was Big Ben's day. Ian Millar and Millar Brooke's day. There are a few Big Ben links that I have not mentioned before:

The Big Ben Memorial Trail, with kudos to all the amazing volunteers |

stewart smithI'm a woodcarver, turned sculptor, and morphed into a pattern-maker for cast metals. These days I hesitate to define my work, avoiding words like 'artist' or 'craftsman'. I just love designing and making things, keeping a bit of time free to downhill ski, paddle my kayak, and sing with my fellow choristers. Archives

November 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed